Installation

To install the criterion package, simply use cabal, the standard Haskell package management command.

cabal update

cabal install -j --disable-tests criterionDepending on how many prerequisites you already have installed, and what your Cabal configuration looks like, the build will probably take just a few minutes.

Getting started

Here’s a a simple and complete benchmark, measuring the performance of the ever-ridiculous fib function.

import Criterion.Main

-- The function we're benchmarking.

fib m | m < 0 = error "negative!"

| otherwise = go m

where

go 0 = 0

go 1 = 1

go n = go (n-1) + go (n-2)

-- Our benchmark harness.

main = defaultMain [

bgroup "fib" [ bench "1" $ whnf fib 1

, bench "5" $ whnf fib 5

, bench "9" $ whnf fib 9

, bench "11" $ whnf fib 11

]

]The defaultMain function takes a list of Benchmark values, each of which describes a function to benchmark. (We’ll come back to bench and whnf shortly, don’t worry.)

To maximise our convenience, defaultMain will parse command line arguments and then run any benchmarks we ask. Let’s compile our benchmark program.

$ ghc -O --make Fibber

[1 of 1] Compiling Main ( Fibber.hs, Fibber.o )

Linking Fibber ...If we run our newly compiled Fibber program, it will benchmark all of the functions we specified.

$ ./Fibber --output fibber.html

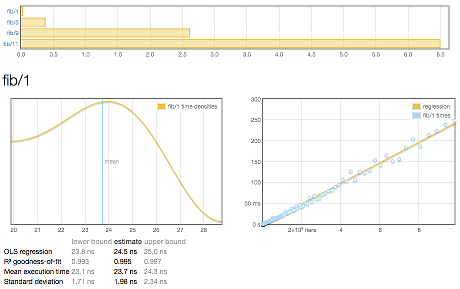

benchmarking fib/1

time 23.91 ns (23.30 ns .. 24.54 ns)

0.994 R² (0.991 R² .. 0.997 R²)

mean 24.36 ns (23.77 ns .. 24.97 ns)

std dev 2.033 ns (1.699 ns .. 2.470 ns)

variance introduced by outliers: 88% (severely inflated)

...more output follows...Even better, the --output option directs our program to write a report to the file fibber.html. Click on the image to see a complete report. If you mouse over the data points in the charts, you’ll see that they are live, giving additional information about what’s being displayed.

Understanding charts

A report begins with a summary of all the numbers measured. Underneath is a breakdown of every benchmark, each with two charts and some explanation.

The chart on the left is a kernel density estimate (also known as a KDE) of time measurements. This graphs the probability of any given time measurement occurring. A spike indicates that a measurement of a particular time occurred; its height indicates how often that measurement was repeated.

Why not use a histogram?

A more popular alternative to the KDE for this kind of display is the histogram. Why do we use a KDE instead? In order to get good information out of a histogram, you have to choose a suitable bin size. This is a fiddly manual task. In contrast, a KDE is likely to be informative immediately, with no configuration required.The chart on the right contains the raw measurements from which the kernel density estimate was built. The x axis indicates the number of loop iterations, while the y axis shows measured execution time for the given number of iterations. The line “behind” the values is a linear regression generated from this data. Ideally, all measurements will be on (or very near) this line.

Understanding the data under a chart

Underneath the chart for each benchmark is a small table of information that looks like this.

| lower bound | estimate | upper bound | |

|---|---|---|---|

| OLS regression | 31.0 ms | 37.4 ms | 42.9 ms |

| R² goodness-of-fit | 0.887 | 0.942 | 0.994 |

| Mean execution time | 34.8 ms | 37.0 ms | 43.1 ms |

| Standard deviation | 2.11 ms | 6.49 ms | 11.0 ms |

The first two rows are the results of a linear regression run on the measurements displayed in the right-hand chart.

“OLS regression” estimates the time needed for a single execution of the activity being benchmarked, using an ordinary least-squares regression model. This number should be similar to the “mean execution time” row a couple of rows beneath. The OLS estimate is usually more accurate than the mean, as it more effectively eliminates measurement overhead and other constant factors.

“R² goodness-of-fit” is a measure of how accurately the linear regression model fits the observed measurements. If the measurements are not too noisy, R² should lie between 0.99 and 1, indicating an excellent fit. If the number is below 0.99, something is confounding the accuracy of the linear model. A value below 0.9 is outright worrisome.

“Mean execution time” and “Standard deviation” are statistics calculated (more or less) from execution time divided by number of iterations.

On either side of the main column of values are greyed-out lower and upper bounds. These measure the accuracy of the main estimate using a statistical technique called bootstrapping. This tells us that when randomly resampling the data, 95% of estimates fell within between the lower and upper bounds. When the main estimate is of good quality, the lower and upper bounds will be close to its value.

Reading command line output

Before you look at HTML reports, you’ll probably start by inspecting the report that criterion prints in your terminal window.

benchmarking ByteString/HashMap/random

time 4.046 ms (4.020 ms .. 4.072 ms)

1.000 R² (1.000 R² .. 1.000 R²)

mean 4.017 ms (4.010 ms .. 4.027 ms)

std dev 27.12 μs (20.45 μs .. 38.17 μs)The first column is a name; the second is an estimate. The third and fourth, in parentheses, are the 95% lower and upper bounds on the estimate.

timecorresponds to the “OLS regression” field in the HTML table above.R²is the goodness-of-fit metric fortime.meanandstd devhave the same meanings as “Mean execution time” and “Standard deviation” in the HTML table.

How to write a benchmark suite

A criterion benchmark suite consists of a series of Benchmark values.

main = defaultMain [

bgroup "fib" [ bench "1" $ whnf fib 1

, bench "5" $ whnf fib 5

, bench "9" $ whnf fib 9

, bench "11" $ whnf fib 11

]

]We group related benchmarks together using the bgroup function. Its first argument is a name for the group of benchmarks.

bgroup :: String -> [Benchmark] -> BenchmarkAll the magic happens with the bench function. The first argument to bench is a name that describes the activity we’re benchmarking.

bench :: String -> Benchmarkable -> Benchmark

bench = BenchmarkThe Benchmarkable type is a container for code that can be benchmarked.

By default, criterion allows two kinds of code to be benchmarked.

Any

IOaction can be benchmarked directly.With a little trickery, we can benchmark pure functions.

Benchmarking an IO action

This function shows how we can benchmark an IO action.

import Criterion.Main

main = defaultMain [

bench "readFile" $ nfIO (readFile "GoodReadFile.hs")

]We use nfIO to specify that after we run the IO action, its result must be evaluated to normal form, i.e. so that all of its internal constructors are fully evaluated, and it contains no thunks.

nfIO :: NFData a => IO a -> IO ()Rules of thumb for when to use nfIO:

Any time that lazy I/O is involved, use

nfIOto avoid resource leaks.If you’re not sure how much evaluation will have been performed on the result of an action, use

nfIOto be certain that it’s fully evaluated.

IO and seq

In addition to nfIO, criterion provides a whnfIO function that evaluates the result of an action only deep enough for the outermost constructor to be known (using seq). This is known as weak head normal form (WHNF).

whnfIO :: IO a -> IO ()This function is useful if your IO action returns a simple value like an Int, or something more complex like a Map where evaluating the outermost constructor will do “enough work”.

Be careful with lazy I/O!

Experienced Haskell programmers don’t use lazy I/O very often, and here’s an example of why: if you try to run the benchmark below, it will probably crash.

import Criterion.Main

main = defaultMain [

bench "whnfIO readFile" $ whnfIO (readFile "BadReadFile.hs")

]The reason for the crash is that readFile reads the contents of a file lazily: it can’t close the file handle until whoever opened the file reads the whole thing. Since whnfIO only evaluates the very first constructor after the file is opened, the benchmarking loop causes a large number of open files to accumulate, until the inevitable occurs:

$ ./BadReadFile

benchmarking whnfIO readFile

openFile: resource exhausted (Too many open files)Beware “pretend” I/O!

GHC is an aggressive compiler. If you have an IO action that doesn’t really interact with the outside world, and it has just the right structure, GHC may notice that a substantial amount of its computation can be memoised via “let-floating”.

There exists a somewhat contrived example of this problem, where the first two benchmarks run between 40 and 40,000 times faster than they “should”.

As always, if you see numbers that look wildly out of whack, you shouldn’t rejoice that you have magically achieved fast performance—be skeptical and investigate!

Defeating let-floating

Fortunately for this particular misbehaving benchmark suite, GHC has an option named -fno-full-laziness that will turn off let-floating and restore the first two benchmarks to performing in line with the second two.

-fno-full-laziness into every GHC-and-criterion command line, as let-floating helps with performance more often than it hurts with benchmarking.

Benchmarking pure functions

Lazy evaluation makes it tricky to benchmark pure code. If we tried to saturate a function with all of its arguments and evaluate it repeatedly, laziness would ensure that we’d only do “real work” the first time through our benchmarking loop. The expression would be overwritten with that result, and no further work would happen on subsequent loops through our benchmarking harness.

We can defeat laziness by benchmarking an unsaturated function—one that has been given all but one of its arguments.

This is why the nf function accepts two arguments: the first is the almost-saturated function we want to benchmark, and the second is the final argument to give it.

nf :: NFData b => (a -> b) -> a -> BenchmarkableAs the NFData constraint suggests, nf applies the argument to the function, then evaluates the result to normal form.

The whnf function evaluates the result of a function only to weak head normal form (WHNF).

whnf :: (a -> b) -> a -> BenchmarkableIf we go back to our first example, we can now fully understand what’s going on.

main = defaultMain [

bgroup "fib" [ bench "1" $ whnf fib 1

, bench "5" $ whnf fib 5

, bench "9" $ whnf fib 9

, bench "11" $ whnf fib 11

]

]We can get away with using whnf here because we know that an Integer has only one constructor, so there’s no deeper buried structure that we’d have to reach using nf.

As with benchmarking IO actions, there’s no clear-cut case for when to use whfn versus nf, especially when a result may be lazily generated.

Guidelines for thinking about when to use nf or whnf:

If a result is a lazy structure (or a mix of strict and lazy, such as a balanced tree with lazy leaves), how much of it would a real-world caller use? You should be trying to evaluate as much of the result as a realistic consumer would. Blindly using

nfcould cause way too much unnecessary computation.If a result is something simple like an

Int, you’re probably safe usingwhnf—but then again, there should be no additional cost to usingnfin these cases.

Using the criterion command line

By default, a criterion benchmark suite simply runs all of its benchmarks. However, criterion accepts a number of arguments to control its behaviour. Run your program with --help for a complete list.

Specifying benchmarks to run

The most common thing you’ll want to do is specify which benchmarks you want to run. You can do this by simply enumerating each benchmark.

./Fibber 'fib/fib 1'By default, any names you specify are treated as prefixes to match, so you can specify an entire group of benchmarks via a name like "fib/". Use the --match option to control this behaviour.

Listing benchmarks

If you’ve forgotten the names of your benchmarks, run your program with --list and it will print them all.

How long to spend measuring data

By default, each benchmark runs for 5 seconds.

You can control this using the --time-limit option, which specifies the minimum number of seconds (decimal fractions are acceptable) that a benchmark will spend gathering data. The actual amount of time spent may be longer, if more data is needed.

Writing out data

Criterion provides several ways to save data.

The friendliest is as HTML, using --output. Files written using --output are actually generated from Mustache-style templates. The only other template provided by default is json, so if you run with --template json --output mydata.json, you’ll get a big JSON dump of your data.

You can also write out a basic CSV file using --csv, and a JUnit-compatible XML file using --junit. (The contents of these files are likely to change in the not-too-distant future.)

Linear regression

If you want to perform linear regressions on metrics other than elapsed time, use the --regress option. This can be tricky to use if you are not familiar with linear regression, but here’s a thumbnail sketch.

The purpose of linear regression is to predict how much one variable (the responder) will change in response to a change in one or more others (the predictors).

On each step through through a benchmark loop, criterion changes the number of iterations. This is the most obvious choice for a predictor variable. This variable is named iters.

If we want to regress CPU time (cpuTime) against iterations, we can use cpuTime:iters as the argument to --regress. This generates some additional output on the command line:

time 31.31 ms (30.44 ms .. 32.22 ms)

0.997 R² (0.994 R² .. 0.999 R²)

mean 30.56 ms (30.01 ms .. 30.99 ms)

std dev 1.029 ms (754.3 μs .. 1.503 ms)

cpuTime: 0.997 R² (0.994 R² .. 0.999 R²)

iters 3.129e-2 (3.039e-2 .. 3.221e-2)

y -4.698e-3 (-1.194e-2 .. 1.329e-3)After the block of normal data, we see a series of new rows.

On the first line of the new block is an R² goodness-of-fit measure, so we can see how well our choice of regression fits the data.

On the second line, we get the slope of the cpuTime/iters curve, or (stated another way) how much cpuTime each iteration costs.

The last entry is the y-axis intercept.

Measuring garbage collector statistics

By default, GHC does not collect statistics about the operation of its garbage collector. If you want to measure and regress against GC statistics, you must explicitly enable statistics collection at runtime using +RTS -T.

Useful regressions

| regression |

--regress

|

notes |

|---|---|---|

| CPU cycles |

cycles:iters

|

|

| Bytes allocated |

allocated:iters

|

+RTS -T

|

| Number of garbage collections |

numGcs:iters

|

+RTS -T

|

| CPU frequency |

cycles:time

|

Tips, tricks, and pitfalls

While criterion tries hard to automate as much of the benchmarking process as possible, there are some things you will want to pay attention to.

Measurements are only as good as the environment in which they’re gathered. Try to make sure your computer is quiet when measuring data.

Be judicious in when you choose

nfandwhnf. Always think about what the result of a function is, and how much of it you want to evaluate.Simply rerunning a benchmark can lead to variations of a few percent in numbers. This variation can have many causes, including address space layout randomization, recompilation between runs, cache effects, CPU thermal throttling, and the phase of the moon. Don’t treat your first measurement as golden!

Keep an eye out for completely bogus numbers, as in the case of

-fno-full-lazinessabove.When you need trustworthy results from a benchmark suite, run each measurement as a separate invocation of your program. When you run a number of benchmarks during a single program invocation, you will sometimes see them interfere with each other.

How to sniff out bogus results

If some external factors are making your measurements noisy, criterion tries to make it easy to tell. At the level of raw data, noisy measurements will show up as “outliers”, but you shouldn’t need to inspect the raw data directly.

The easiest yellow flag to spot is the R² goodness-of-fit measure dropping below 0.9. If this happens, scrutinise your data carefully.

Another easy pattern to look for is severe outliers in the raw measurement chart when you’re using --output. These should be easy to spot: they’ll be points sitting far from the linear regression line (usually above it).

If the lower and upper bounds on an estimate aren’t “tight” (close to the estimate), this suggests that noise might be having some kind of negative effect.

A warning about “variance introduced by outliers” may be printed. This indicates the degree to which the standard deviation is inflated by outlying measurements, as in the following snippet (notice that the lower and upper bounds aren’t all that tight, too).

std dev 652.0 ps (507.7 ps .. 942.1 ps)

variance introduced by outliers: 91% (severely inflated)